Tobiáš Waller

Translation: Karolína Průšová

What is consciousness? What is the unconscious? What is mind? These and many other questions are asked by the performer Arman Kupelyan together with the creative team of the production Playground of the Unconscious Self, which concluded the third day of the festival and brought the audience closer to the topic of the unconscious. Kupelyan created an original character with which he demonstrates fragments of his own inner world. At the same time, he creates a dialogue between the personified unconscious and the person in whom it is trapped, or with the audience itself.

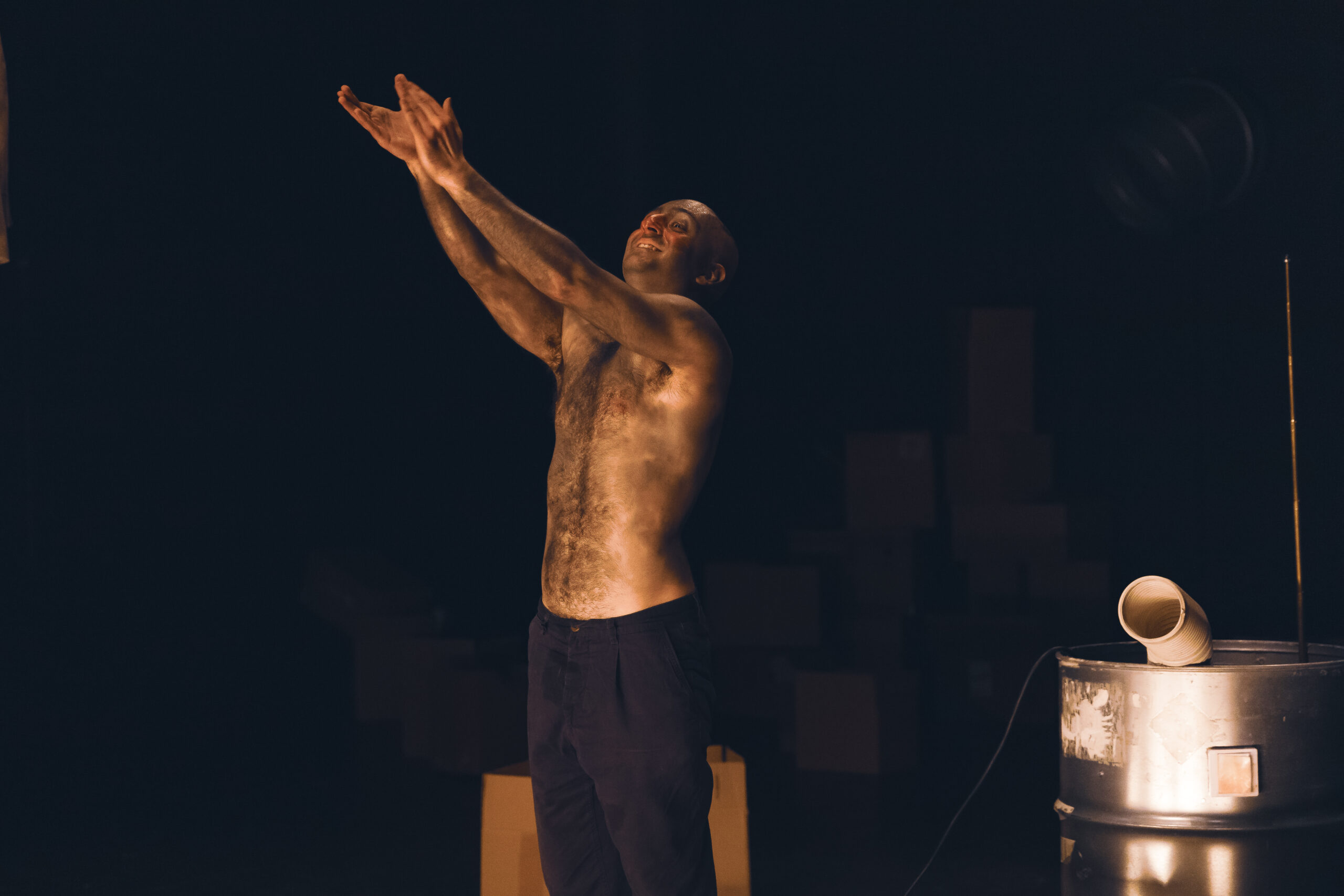

In a production that uses elements of pantomime, non-verbal theatre and clowning, the performer embodies the unconscious as a kind of warped and bleakly lonely character, which is, however, not desperate. Its appearance, which may evoke a goblin or a disabled person, points out that the unconscious is something neglected and ignored. Something that has not been given the proper development and growth. But something that is pleasant, honest and gentle. Kupelyan reveals his inner self and offers an intimate look at a series of personal experiences. He guides the audience from childhood experience and traumas, through sexual desires and love, to dependence on others and the need to share his life. In doing so, he opens up his own shared play as a sad clown. It is as if we are all the time visiting the alien unconscious in which the character dwells.

Kupelyan created the character together with dramaturg and co-director Emil Rothermel with the idea of the heaviness of the mental processes taking place inside us. He drew on the principle of clowning and butoh dance. Its physical appearance is made of a hunched back, wild clown mimicry and gesture, or even infantile movement vocabulary. Its personified unconscious, that is, a hunched and dirty man, stumbles and hobbles around, having apparently never been allowed to do anything else.

He set the character of the darkened clown directly inside the mind of a man. This is matched by the simple but perfectly functional set design (Lidya Arinna Emir, Alexandra Chernomashyntseva), which is composed of objects that may act randomly on the stage, but they are in a way crucial for the play. In the right rear part of the stage there is a table with a chair, at which at the beginning a man falls asleep, in whose mind and the unconscious the rest of the action takes place. In the left rear part, there is a disparate pile of boxes from which the clown pulls various objects with which he plays his game. The scene is completed by a couple of massive metal pipes and a framed portrait of the man from the introduction. During his play, he also uses a dream machine constructed from a tin barrel, an aerial and a switch, which triggers the dream production. For the clown’s play, a darkened and silent space is created, reminiscent of a stocked cellar or attic full of memories, thoughts, traumas and desires.

Although Kupelyan’s character is built on the principle of pantomime, it does speak. It is clear that the character has a problem with it at the beginning, and it takes it quite a while to overcome the difficulties of articulation and the actual creation of words and sentences. But this fully supports the interpretation that the unconscious is something forgotten and lonely. Just as newly born children squint at the light and learn to speak, the clown is initially taken aback by both the lights and the audience itself, with whom he interacts all the time. This creates a comic line, which, even after almost an hour, is still entertaining. He asks the audience if they are his friends and lets them encourage him in his play. It is as if his primary motivation is the presence of the audience and the genuine interest of someone who has never met people before to explore who they are.

He lets himself to be challenged and gradually begins to show off more and more. He enjoys the attention and graduates by changing from a shy and wide-eyed mime to a more confident one. Towards the end, he asks for music and dances freely to the rhythms of electronic music (Štěpán Plíva). With the ringing of the alarm clock, however, he politely and humbly says goodbye, leaves and concludes his dream play, with which he has entertained the audience and himself. With a quiet and calm departure, he seems to confirm the ephemerality of the moments when our own minds manifest and prevail over the rational.

Kupelyan has created an original character that he can lead and develop with unquestionable confidence and fragile delicacy. Through his personal poetics, he looks at the themes of the mind and the unconscious, which he diligently processes and visibly imprints on the character of the clown. In an intimate, quiet and almost warm production, he fully plays his clown, giving the impression that the sad and fragile mime is and always has been himself.

Faculty of Music, Academy of Performing Arts in Prague – Arman Kupelyan: Playground of the Unconscious Self. Directed by Arman Kupelyan, Emil Rothermel, dramaturgy by Emil Rothermel, choreography by Arman Kupelyan, set and costumes by Lidya Arinna Emir, Alexandra Chernomashyntseva, music by Štěpán Plíva. Written from the performance on 10 June 2022 at DISK as part of the Zlomvaz festival.

PHOTO: Juan David Cevallos